Mexico City and its Mystical Allure to Radical Artists

After ‘The Great Depression’, artists escaped to Mexico for creative freedom. Almost a century later, unrest and discontent is still felt by younger generations today, but what is their escape?

Contents:

1. Historical Perspective

2. Exodus to Mexico

3. Mexico and its Allure

4. The Surrealists

5. Refuge in Mexico

6. Authors and The Beat Movement

7. Refuge in context today

Historical Perspective

What do artists and young people today have in common with artists from the past? And where does Mexico City come into this?

The Wall Street Crash (1929) was a momentous event that affected people of all walks of life. Low interest rates created a culture of speculation on the stock market with ordinary working class people looking to make gains. It began with rising unemployment in the mid 1920s which led to a decrease in stock prices. Investors (which included both the everyday man and richer folk) quickly borrowed more than they could lose to invest in these stocks. A total of $14 billion was lost. This not only affected the US but also forced the UK and Europe to fall into a major economic depression. More people lost their jobs with any work hard to come by. Life was dire and soon a Second World War was approaching.

Following the 1929 stock market crash creatives were looking for an escape. The artist’s plight is an odyssey even more arduous when the cost of living crisis wave is crashing over and pulling you under. (Familiar?) Here begins the exodus of artists and pioneers, bohemians and anarchists, eccentrics and rebels on a journey to their promised land.

The mass exodus to Mexico City mirrors the same desire for freedom in self-expression we’re experiencing now. Our generation was promised the moon. With hard work we were told we could achieve whatever we set our minds to. Yet, in contrast with our early childhoods, life is harder, our basic necessities more costly, and we’ve become the product of big tech companies. We’re no longer their customers.

With an increasing disillusionment in the current state of the world, we are pushing to subvert social media restraints. No longer allowing ourselves to be chained to an algorithm where our data is the product. People have been cancelling Spotify subscriptions because the algorithm repeatedly pushes the same type of music, then buying iPods, music tapes or vinyls to curate a library with a more personal touch. Alternatively, buying old brick phones from the early 2000s because of a general fatigue with apps, notifications and social media.

People want to switch off and slow down. People want freedom to experience music, art and life on their own accord. Not dictated by a company who decides what they think is popular and profitable for their own gain. We are shirking off technology and its grip on how we live our lives.

Exodus to Mexico

There were several waves of inquisitive minds making their way over to Mexico. In the 1920s/30s we have those fleeing an economic depression, wrapped up warm with an interest in the consequences of the Mexican Revolution in 1914 and Diego Rivera’s international claim as a Cubist in Paris. In the 1940s, those fleeing Nazi occupied Europe and persecution. With, finally in the 1950s, those fleeing from a suffering of post-war hollowness and dread, looking for a hint of wonder left in the world.

What attracted these artists to the mysticism of Mexico? Guatemalan poet Luis Cardoza y Aragón, captured the essence of this curiosity for Mexico in a letter to André Breton in 1936:

“We are in the land of convulsive beauty, the land of edible delusions… a place for the mutable, the disturbing, the other death, in short, a land of dream, unavoidable by the surrealist spirit.”

Following Breton’s subsequent visit, it seems the French poet himself:

“admired Mexico for the ‘purity’ of its primitive cultures and saw in the country the promise of a ‘land of freedom’.”

Peggy Guggenheim, amongst others organised and covered the transportation and expenses to evacuate artists and politicians under threat by the Nazi regime. The evacuees included Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, André Breton alongside many others. The US refused to accept the individuals leaning more towards a left-wing and Communist ideology. Whilst Mexico’s president, Lázaro Cárdenas, offered citizenship to all political refugees at the onset of the Second World War. As such, the artists who previously congregated in Parisian cafés were now welcomed with open arms across the Atlantic Ocean after the Nazi invasion in June, 1940.

Mexico and its Allure

It was André Breton once again, who coined the phrase in referring to Mexico City, “the utmost Surrealist place par excellence.”

And it was Octavio Paz (a Mexican poet and diplomat) who accurately describes the soul behind the movement:

“Surrealism was not merely an esthetic, poetic and philosophical doctrine… It was a vital attitude. A negation of the contemporary world and at the same time an attempt to substitute other values for those of democratic bourgeois society: eroticism, poetry, imagination, liberty, spiritual adventure, vision.”

Any explorers of a new society and culture, will initially be most attracted to the exotic appeal of the new world. This applied to many counterculture artists who found their way over in Mexico from the 1920s to the 1950s. Many Americans and Europeans were enthralled by the contrast of a deeply spiritual and mystic land, hiding behind “a thin veneer of westernism.” It was entirely different to anything they had ever experienced before. Especially due to the local people’s reverence for the dead as opposed to the living. With pre-Columbian rituals and myths still very much alive in a world that seemed to be slowly decaying back home due to fascism and war.

The Surrealists

The artists attracted to Mexico City for its close connection to mythology and a different way of thinking, ushered in the promise of a new Surrealist movement to follow in the footsteps of the interest and acclaim previously won in Paris. Wolfgang Paalen and César Moro played a key role in organising The 1940 International Exhibition of Surrealism in Mexico City. This exhibition was a catalyst in the development of modern Mexican art, and was conceptualised due to the artists admiration of pre-Columbian art. Pre-Columbian art and objects exhibited at this event were manifestations of the soul that first captured their hearts on arrival in Mexico.

However, art historians upon further research, have outlined the friction felt between the international and local artists at this event. With predominantly international art hung up on the walls, and the work of famous Mexican artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera shown in the international, not local, artist section. Moreover, César Moro was pushing his own agenda of uniting ancient traditions and pre-Columbian art with his idealised world in order to construct a new world order as opposition in the face of fascism. Moro, as such, criticised local artists of selling themselves out and their ideals for profit by focusing on folklore instead of his idealised construct.

Every story is overwhelmed with the narrative and perspective told through the eyes of a minority of newcomers. There remains an importance in drawing attention to the realities of the people of the land. Even Breton’s coinage of Mexico being the most surrealist country, at its core, reveals how intangible and obscure Mexico is to these newcomers. Numerous writers after their journeys to Mexico, such as D.H. Lawrence, Graham Greene, Henry Miller and Aldous Huxley, would go on to author books who according to Octavio Paz, never fully grasped onto the soul of the country and its people. Frida Kahlo herself, rejected the Surrealist label after her exhibition in Paris in 1939. Wishing to align herself more with local Mexican sentiment.

Chloe Aridjis, a Mexican-American author (whose family was acquainted with Leonora Carrington) puts this further into perspective, questioning whether Mexico is truly ‘surrealist’ or simply a former colony where modern life and habits have sprung up unevenly amongst deeply entrenched rituals and history. Yet she concludes with a feeling that there’s something more unique about “the Mexican imagination.”

Refuge in Mexico

Nevertheless, despite Paalen, Moro and other artists breaking away from Breton’s new Surrealist movement. The Surrealist Exhibition in Mexico City attracted a flurry of fresh new artists in the early 1940s, those fleeing the Second World War were: Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Benjamin Péret and Kati Horna among others. These new creatives would be the ones to allow Mexican culture and pre-Columbian art to transform them and their work, rather than forcing it to become an idealised notion. They drew inspiration from such traditions of tarot, alchemy, astrology and the occult.

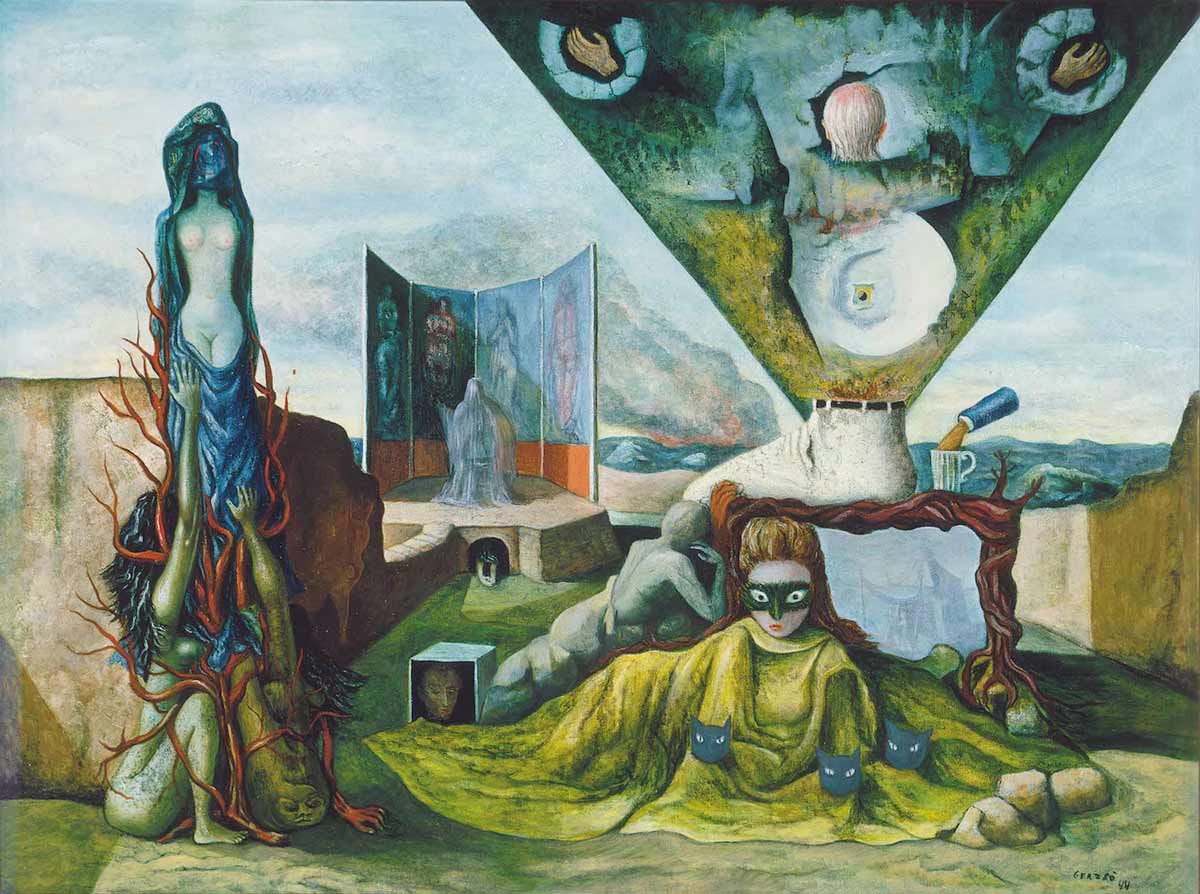

Remedios Varo’s home soon became a hub of Surrealist influence in Mexico City, where she would invite anyone looking for company or money, and host multiple dinners and parties. Even contacting random names she would find in a phone book. Gunther Gerszo would paint the work ‘The Days of Gabino Barreda Street’ to immortalise this scene (picture at the top of this article). Varo’s house became a refuge for the young artists coping with their own personal hells as a result of the Nazi invasion in Europe. This was their antidote to the hollowness and dread of war, and they all became close friends uniting in their common plight.

Authors and the Beat Movement

Henry Miller, Aldous Huxley and Gabriel García Márquez (who was a journalist in Mexico in the 40s/50s), embarked on an odyssey in Mexico exploring their own artistic freedoms and experimenting with their craft. They were escaping social injustices and political critique. Miller specifically was exploring issues of capitalism, freedom and social constraints. What better place to write than Mexico City the Mecca of counterculture creatives?

People were thirsty for an opportunity to disconnect from common thought. Enter the Beat Movement in the 1950s, membership which included the likes of Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs. Kerouac like Miller wrote about freedom ad opposing societal norms (with the book ‘On The Road’). Ginsberg protested the conformity and materialism of post-war America. Whilst Burroughs, explored altered states of consciousness and an expanding awareness induced by drugs (‘Yagé Letters’). The Beats’ focus was on both marginalised voices and bohemians living on the fringes of society, and Mexico’s relaxed view on drug use as opposed to the US. This experience is what contributed to work on liberation and spiritual exploration.

Refuge in context today

Do we still have a Gabino Barreda Street? Or a Camden, or a Shoreditch, or a Mitte in the 90s during the fall of the Berlin Wall?

Life changed significantly with the arrival of the World Wide Web in 1993, Twitter in 2006, YouTube in 2007 and social media in the early 2010s. Until the main requirement to be relevant became having a personal brand, something your viewers or followers could relate to if you wanted an audience to share your work. This prerequisite is only a measure companies use to control users. They choose to no longer filter by quality, but by the capacity users have to become their mouthpiece for selling their products.

Were we delusional before when we said the art or the work wasn’t about us? Common sense would dictate an artist’s experiences and beliefs are surely intertwined with their work. Was the apparent display of detachment or humility just a mask?

I would disagree, because in order to fit in now you have to create the same trending content like everyone else. TikTok and Instagram influencers are becoming disillusioned with their work. What they started in hopes of building a community to share what makes them happy, soon turned into a need of regurgitating the same content and talking about the same topics. They end up running like caged mice in a wheel for those next 100, 1000, 10,000 followers and likes. To what end? They build a platform they can no longer be genuine on or they will lose everything.

So where is our escape now? It can’t be in social media. The enshittification of online services has reached new heights, where poor quality services only serve the purpose of presenting ads at every click. So where is it? Some move to London, Berlin, Paris, Amsterdam but the cost of living crisis means fewer and fewer artists can truly live off their work. Even then, the majority have a social media platform so they can feed themselves.